How Not to Localize Your Game: a Case Study

Released in 2019 in South Korea and 2022 in other parts of the world, Lost Ark is an action MMORPG in the tradition of World of Warcraft and Diablo, offering a massive virtual world filled to the brim with quests, characters, and monsters. Since its global release, the game has ranked consistently among the most played games on Steam and has received favorable reviews across the board.

However, Lost Ark is also a prime example of how game localization matters in upholding the quality of the game—and how failing to localize your game properly can significantly deter player immersion. Despite being one of the most played games on Steam, Lost Ark is host to a number of translation and localization errors.

Today, we’re taking a look at some of the mistranslations and localization failures in Lost Ark as a case study of how such errors can inhibit player immersion in the game and thus impact the gamer community’s attitudes toward the game and its publisher/developer.

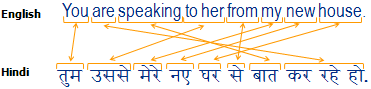

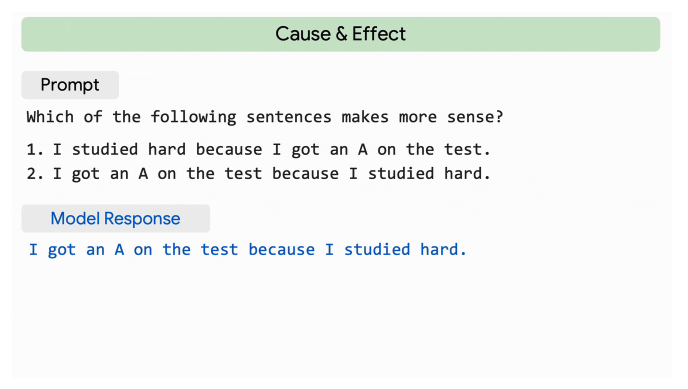

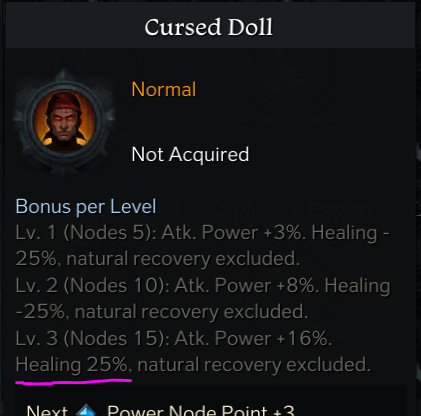

Cinematic Subtitles

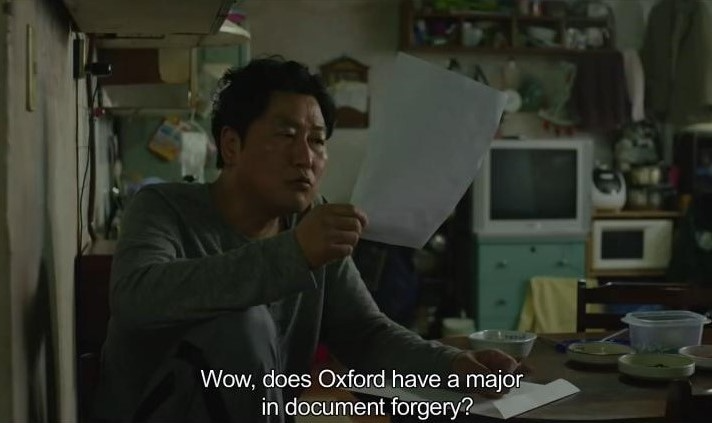

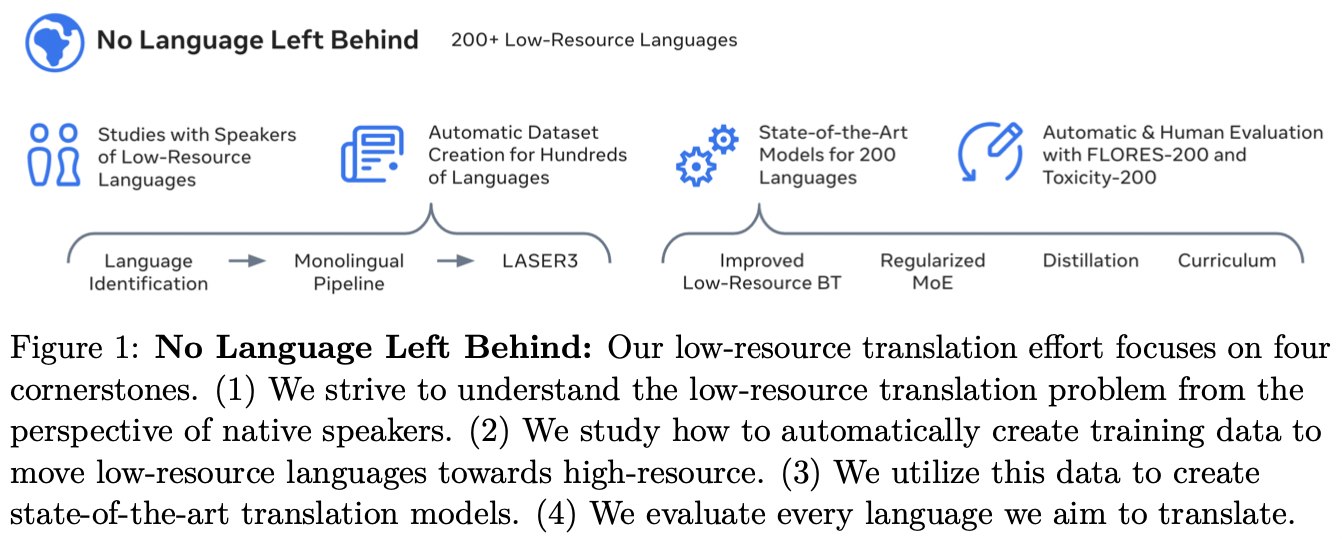

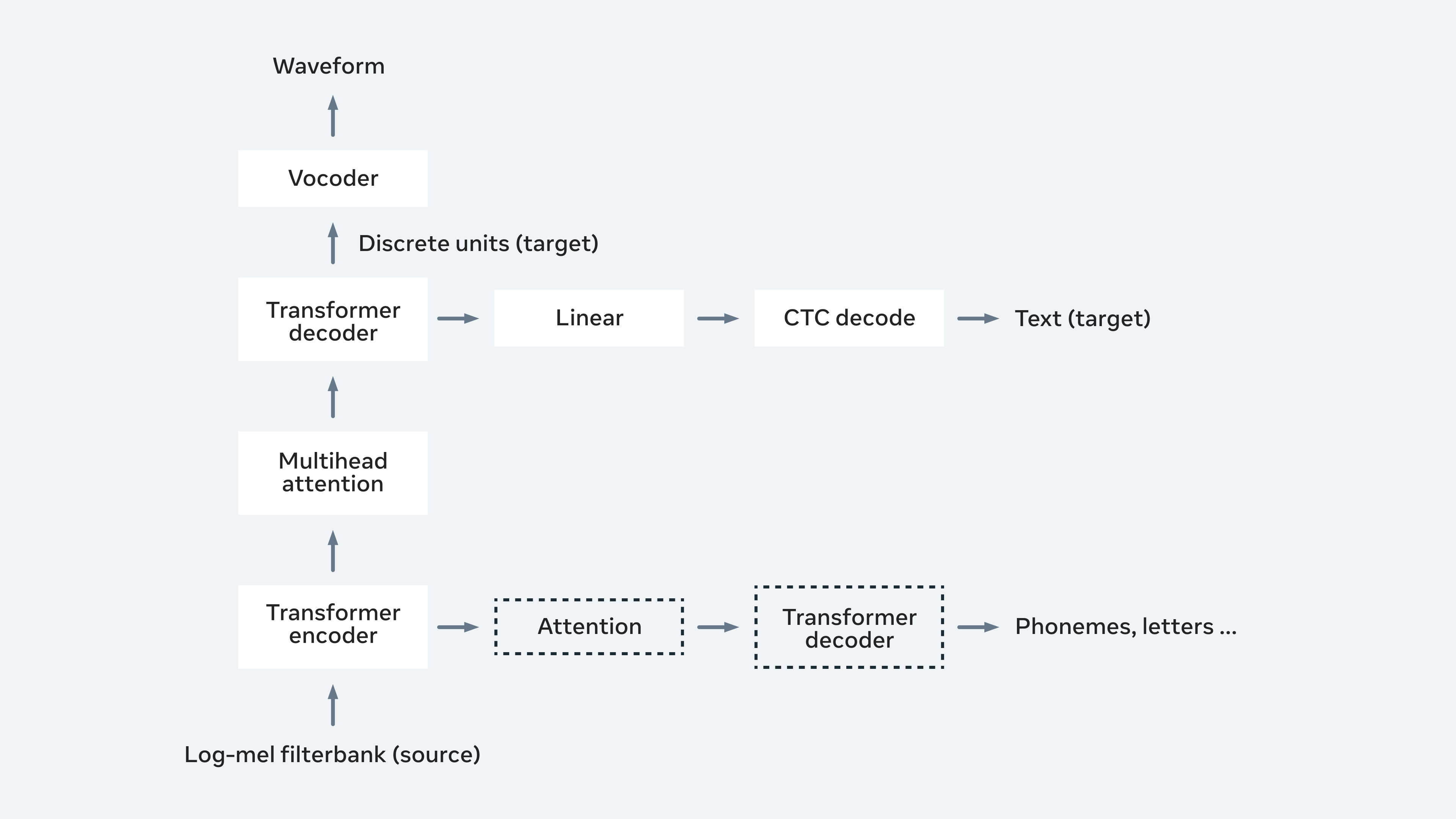

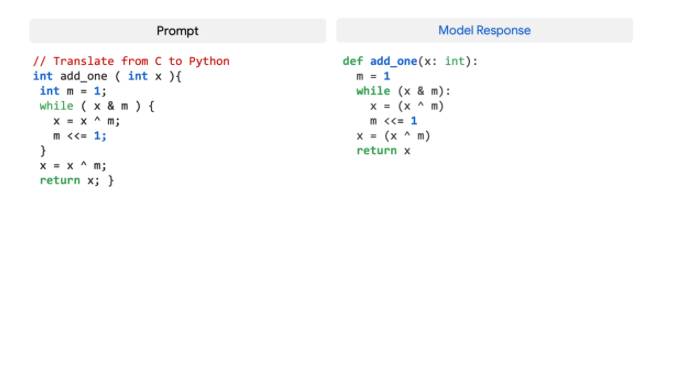

In a cinematic short released for Lost Ark’s South Bern World Quest, a dialogue between a battalion and their commander has been mistranslated, catching the attention of some Lost Ark fans. Here is a screenshot of the mistranslation:

Image Credits: Atramedes, “Chaos Throme – South Bern World Quest – Lost Ark Türkiye Topluluğu

The sentence “We are the window of Bern!” makes little sense. What does it mean to be the window of something? In fact, it seems counterintuitive for a troop of soldiers to call themselves a window: an object designed to let things through and penetrate. The original dialogue in Korean is “우리는 베른의 창!”, which, when translated correctly, means “We are the spear of Bern!” The mistranslation is due to the fact that the word 창 (chang) is a homophone meaning both spear and window.

The word for spear was actually translated correctly a mere two sentences ago, when the commander tells the troop, “Knights of the Sun, hold the spear!” Of course, this sentence comes with its own translation problems; given the context, spear should be in the plural form, given there are dozens of knights. Furthermore, “hold” isn’t the right word here; perhaps “grasp your spears” or “hold up your spears” might’ve been a smoother-sounding translation.

Image Credits: Atramedes, “Chaos Throme – South Bern World Quest – Lost Ark Türkiye Topluluğu

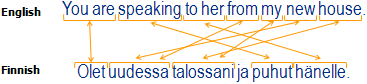

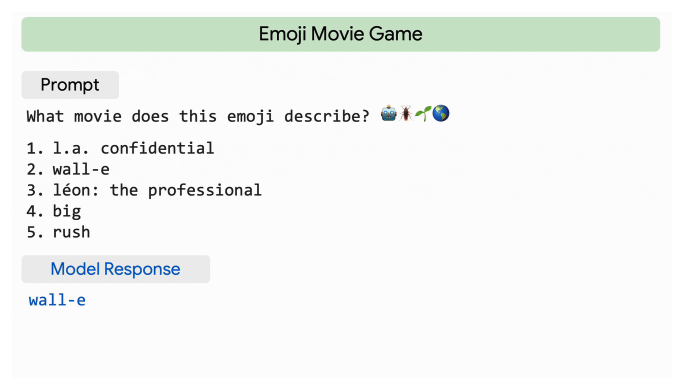

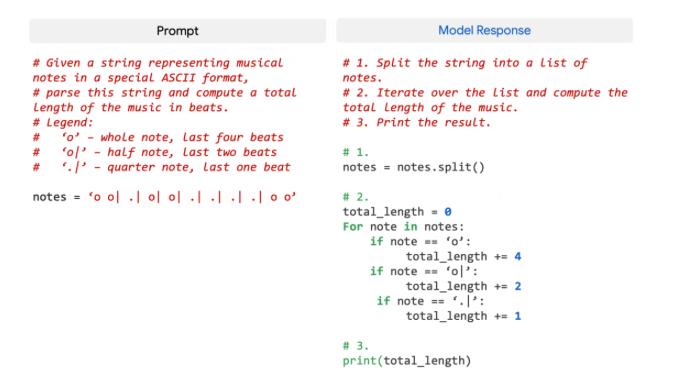

In-Game Dialogue

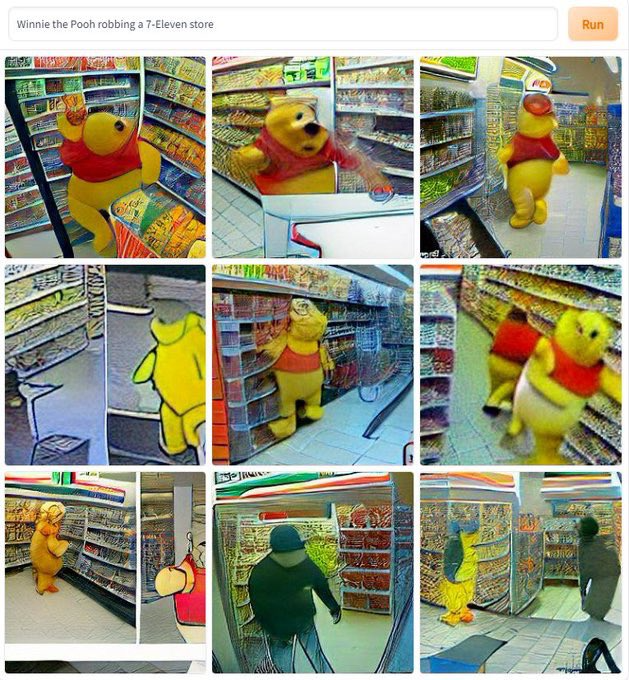

If cinematics—perhaps the most carefully crafted representations of any given game—are riddled with translation errors, it’s fair to assume that the actual game itself will be host to many, many more. That is certainly the case with Lost Ark, whose in-game dialogue falls short at times, like in this mistranslation:

Image credits: https://theqoo.net/lostark/2083519053

Here, the dialogue isn’t actually referring to a cow. The original dialogue for this scene is “소, 솔라스님!”, in which the word 소 (so, meaning cow) doesn’t actually signify cow, but rather is used to express that the speaker is, in fact, stuttering. The correct translation, then, would be “So… Solas!” (Note that the name Solas has also been mistranslated as Solaras.)

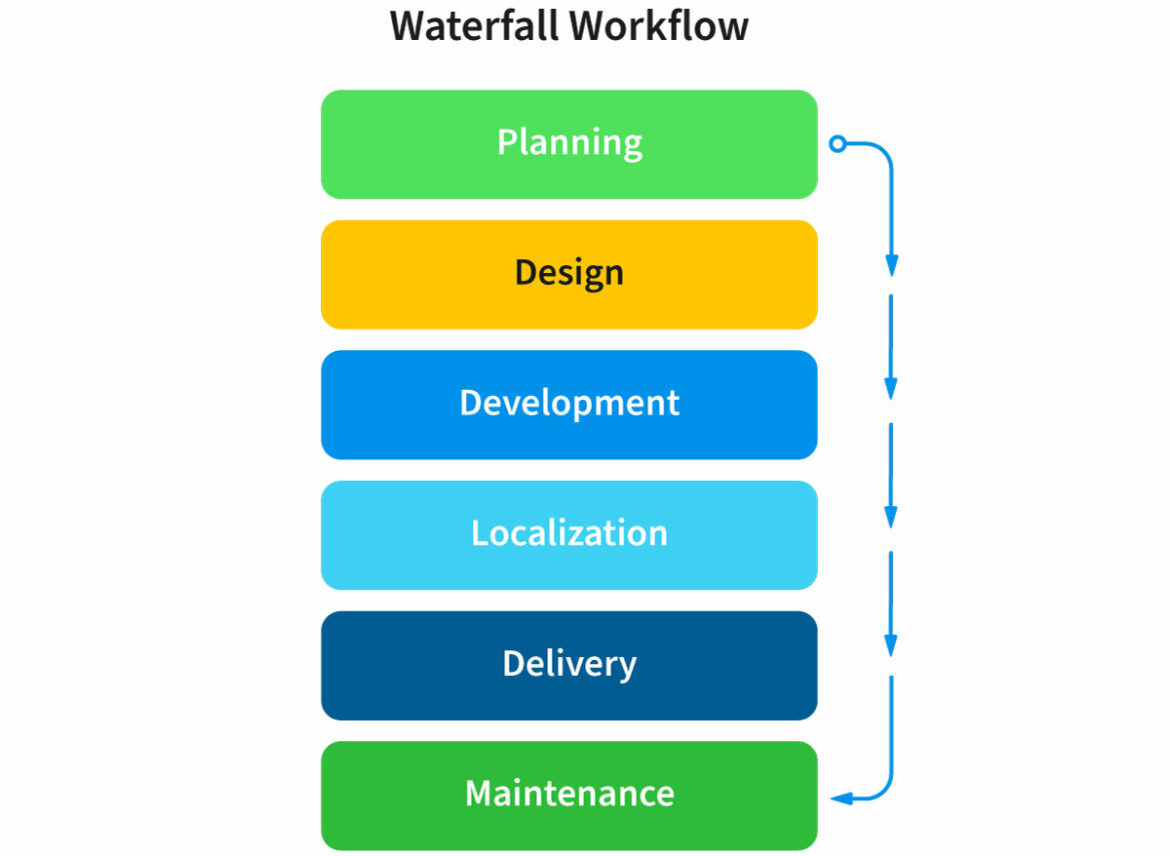

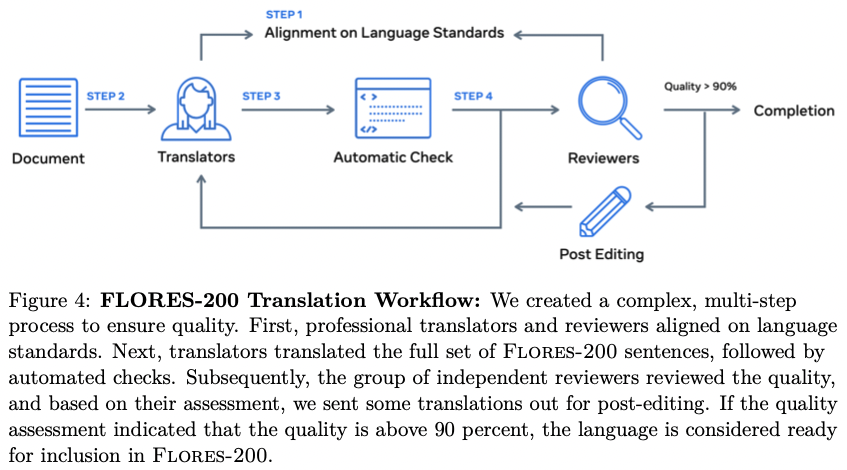

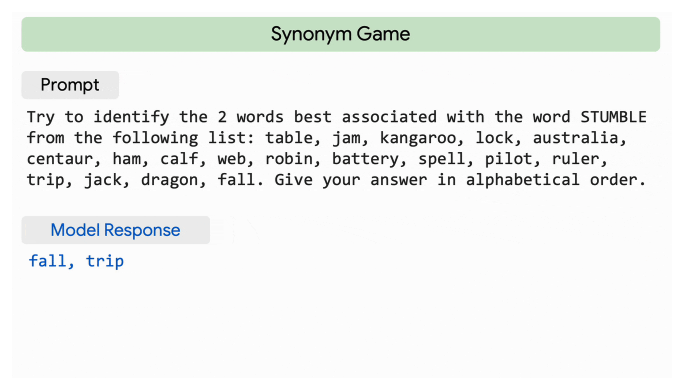

UI Localization Errors

What Lost Ark fans have most complaints with is the game’s general UI localization, which has sparked intense debates and beef sessions on the game’s online forums, like this massive thread on localization errors, as well as this thread on translation and localization errors.

Game UI localization is an especially difficult task to accomplish, not only because game UIs are encoded and displayed in very different settings and through different programs, but also because testing them and checking for errors take up a great deal of time.

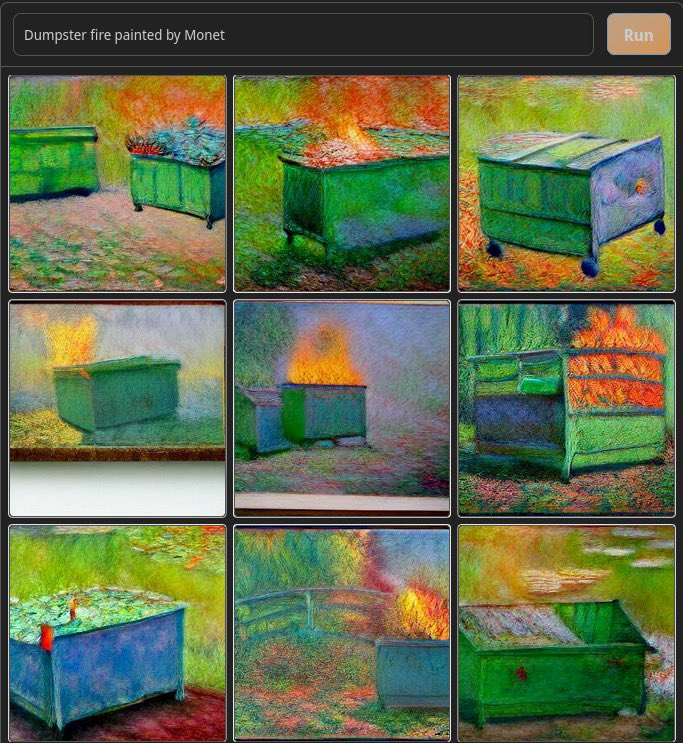

There are issues with consistency in orthography, seen in the pictures below:

Image credits: Ragestyles, Lost Ark Forums

Image credits: Faranim, Lost Ark Forums

On the same page, the same name (벨렌) is spelled Bellen and Velen; on another page, it’s Selen and Celene. It’s clear that the localization has been automated, or that different translators were involved in translating different parts of the game interface. Such inconsistencies can confuse the player—are Celene and Selen different character, or are they different spellings for the same person? What if a quest directs the player to Selen, but the player can only locate Celene?

Also note that, in the former example, the land of 베른 is spelled Vern, not Bern, as was the case in the cinematic. Turns out, Vern is the official spelling of the location for most versions of the game that has been published in most North American and European countries. Such inconsistencies inhibit player immersion and interest in the game, leading gamers to doubt the game and its developers’ QA methods and their sincerity to the game.

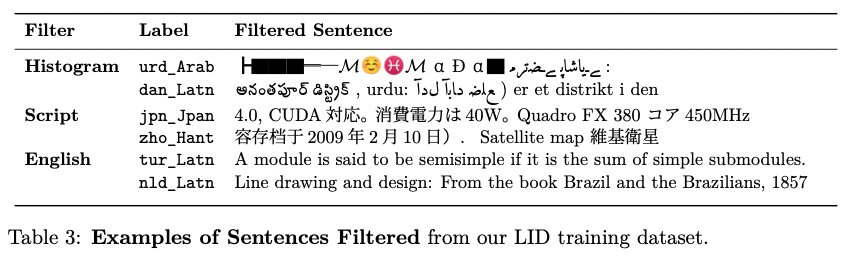

Inconsistencies are also spotted in item names:

| Item Name 1 | Item Name 2 |

|---|---|

| Job Offer Wallpaper | Help Wanted Poster |

| Memoirs of Avesta | Avesta Journal |

| Timeworn Fighter’s Blade | Timeworn Gladiator Blade |

| Amalone’s Diary | Amalone’s Journal |

| Heavy Walker Report | Report on Heavy Walker |

As was the case with inconsistencies in character names, inconsistencies within item names also confuse players. It’s difficult to discern whether Timeworn Fighter’s Blade is the same item as Timeworn Gladiator Blade (surprise: they are different names for the same item!) These errors betray the lack of proper localization on the part of Lost Ark. It seems that there were no glossaries in use to ensure that different translators could render item names in standardized, consistent manners.

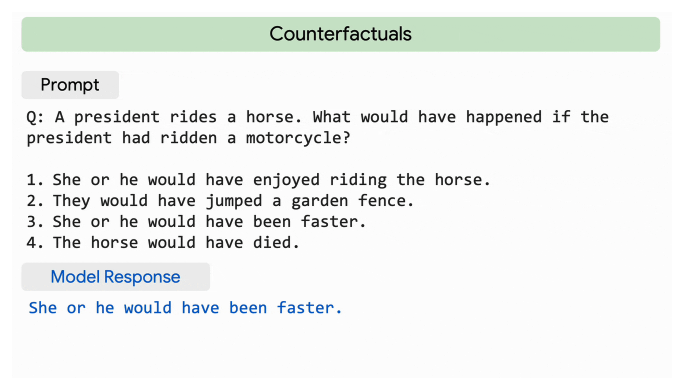

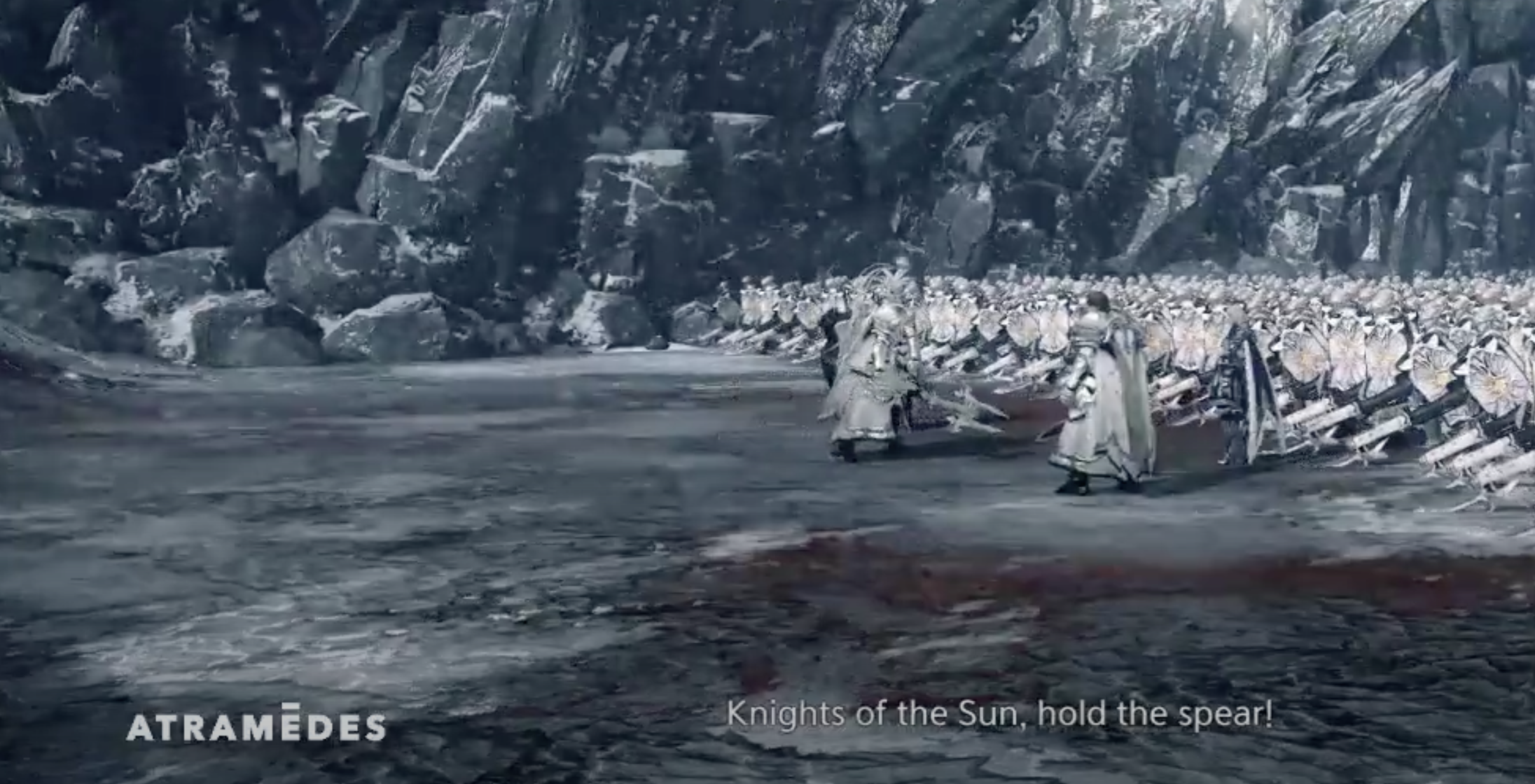

In some cases, errors in localization directly impact user gameplay in rather detrimental ways:

Image credits: Ragestyles, Lost Ark Forums

In omitting a minus sign in front of 25%, the Cursed Doll item seems to be an optimal choice, as it provides 25% additional health at level 3. However, the healing is actually reduced by 25%. Major errors like these directly impact gameplay, as they pertain less with the storyline and more with the actual mechanics of the gameplay itself.

Quality of Translation

Lost Ark also employs a number of ungrammatical or awkward translations that detract from the storyline and gameplay. A good example of this is the abbreviation of the word “level”—an integral component of in-game characters—as “LV”, not “LVL”. The former is a Koreanized abbreviation used on the peninsula, and the latter is what the Anglosphere is more familiar with.

Other seemingly minor problems, yet with major ramifications, include frequent spacing errors (spaces where there should be none, and no spaces where there should be one) and capitalization issues.

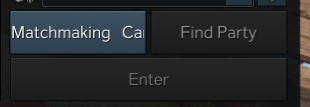

Note that the button says “raid Quit”, instead of “Quit raid” or “Exit raid”. Assuming from the word order, the mistranslation seems to be a direct, word-by-word translation from Korean. Image credits: Ragestyles, Lost Ark Forums

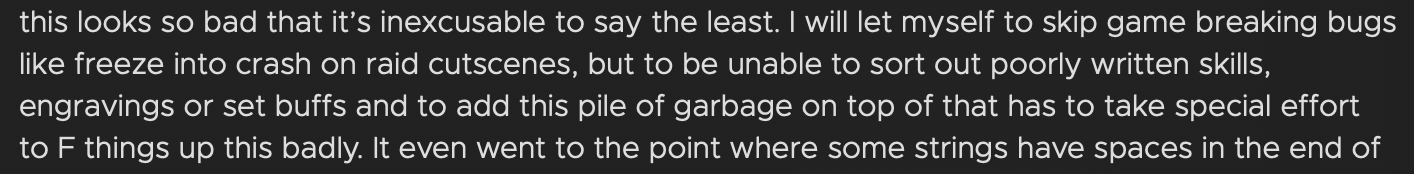

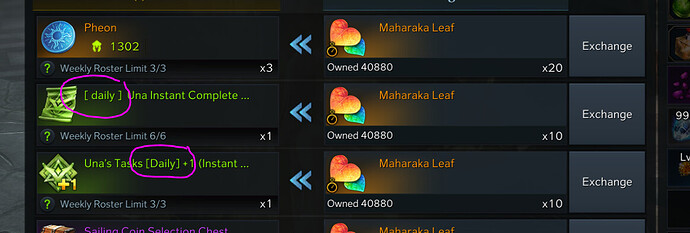

An example of user feedback regarding improperly localized gameplay. Image credits: Wilczasty, Lost Ark Forums

An example of a missing spacing that hinders legibility and gameplay immersion. Image credits: Ragestyles, Lost Ark Forums

More grammatical mistakes spotted by users. Image credits: Ragestyles, Lost Ark Forums

An example of a UI error that failed to take into account how word length expands when translating from Korean into English. Image credits: Ragestyles, Lost Ark Forums

Many of these issues have now been fixed, but only after leagues of users pleaded the developers with pages of screenshots taken of all sorts of mistranslated strings and poorly localized interface components. While Lost Ark should be commended for its willingness to admit to its mistakes and reflect user feedback in its localization process, this is an inefficient way to correct its mistakes. It’d be much better not only for its developers but also its player base to solve these problems before the game even went public.

Here at Sprok DTS, we offer consultations for game developers and publishers to ensure that localization is taken into account from the early stages of game development. Our linguists work directly with companies so that their player base can immerse themselves in the games without being distracted by mistranslations or localizations errors, big or small.

Expand your possibilities with Sprok DTS’s professional, experienced localization services.